From the Asia Times Online:

By Raja Murthy

MUMBAI - Paradise was buried under a vast, cataclysmic mud flow that struck Ladakh district, the beautiful Shangri-la in the Indian Himalayas, last week, killing over 160 people in and outside Leh, the area's main town.

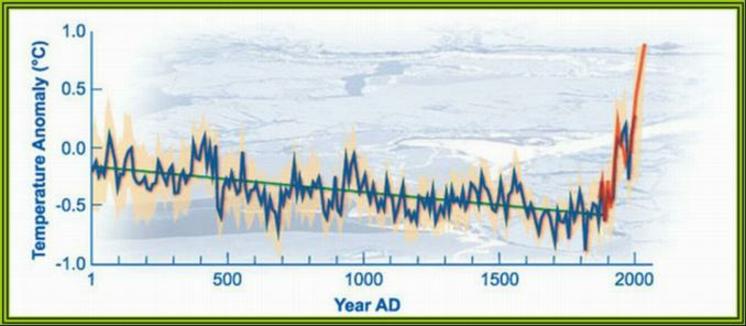

Flash floods and landslides near Leh, which in two hours also destroyed two decades of infrastructure growth, unleashed questions about the fatal effects of pollution and shortsighted economic development on millennia-old sensitive ecological systems. Leh has become a terrible warning about global warming.

The disaster struck Leh and nearby villages early on Friday, just after midnight. According to accounts, a wave of mud 20 meters high and several kilometers wide hit Choglamsar village, practically carrying it away, then smashed the village into Leh town about six kilometers distant.

Television pictures from the state-run Doordarshan, after the disaster the sole media link to Leh, showed scenes seemingly straight out of Pompeii, with mud substituting for the lava from Mount Vesuvius that destroyed the Roman town in 79 AD. It was a chilling sight: a wave of thick mud, still almost two meters high, eerily lurching along a deserted street like a hungry, undulating snake.

The monster waves left behind smashed houses, a white pick-up van crumpled like tissue paper and, the worst sight for those in the area, arms and legs of people buried alive seen sticking out of the deadly mud.

Hundreds of foreign tourists, including 100 Germans, were stranded in Ladakh district, one of the most popular destinations in north India. August is the peak tourist season in this remote area, which has only a brief yearly window, from June to September, of easy access to the outside world. As of August 10, the Indian armed forces had rescued most of the tourists.

The mud tsunami appears as nature's furious response to a fragile ecosystem being messed about with for decades. Development, infrastructure changes, and agricultural experiments to "green-up" the area by the army, government, private businesses and institutions have fractured the simple, traditional, nomadic lifestyle of Ladakh and its Indo-Tibetan culture.

"The Leh calamity is the latest devastating effect of unstable climatic change," said Vandana Shiva, the globally renowned environmental scientist, agriculture activist, particle physicist and director of the New Delhi-based Research Foundation on Science, Technology, and Ecology. She said similar landslides had happened in 2005 in Ladakh but went largely unnoticed because no one died.

"There's an attempt on now to mystify what is happening in Ladakh, attributing it to cloudbursts, for instance, but it’s basically part of the global problem of pollution and chaotic climate conditions," Shiva told Asia Times Online while on a field trip to Dehradun town in the Himalayan foothills.

Shiva, who bore the misfortune of trying to locate her friends missing and feared dead in Ladakh, was entitled to feel vindicated by the Leh disaster. Her report in May 16, 2009, "Climate Change at the Third Pole", predicted impending disaster in the region:

Heavy rainfall which was unknown in the high altitude desert has become more frequent, causing flash floods, washing away homes and fields, trees and livestock. Climate refugees are already being created in the Himalayas in villages such as Rongjuk. As one of the displaced women said, "when we see the black clouds, we feel afraid.

Ladakh was mostly under dark clouds in freakish weather when I arrived there exactly a year after her report was released, on May 16 (see Trouble in India's Shangri-La Asia Times Online, June 24, 2010). It was often rainy and bitterly cold in the peak of the region's summer, including snowfall one morning that astonished the locals.

I disembarked at the Kushok Rimpochee airport in Leh, amid a spectacular Himalayan setting. But now, mere weeks later, television images from the tiny, picturesque airport symbolize sudden death and desperation. Parts of the tarmac have been smashed like a roll of pancake. Hundreds of people squat inside the airport as Indian Air Force planes ferry relief personnel and material. The stranded include migrant workers, after many of their employers became paupers overnight.

The streets in Leh that I had walked about months earlier - past quaint Tibetan curio shops, cafes, adventure tourism agencies and sundry little establishments serving an international clientele - will have to be rebuilt from ruins, the truth of the impermanence of all things made brutally evident.

Leh and the rest of Ladakh, like in Tingmosang village where I spent three weeks, are not built to withstand the effects of heavy rain. Most houses in this largely high altitude desert - averaging about 3,352 meters above sea level - are built out of fragile wood and clay. The gray-brown soil imbues the barren, stunning landscape with its curious hues, set against the backdrop of the Greater Himalayan ranges of Zanskar, East Karokaram and Ladakh.

The August 6 mud tsunami was the deadly offspring of intense, unseasonal rain, a fierce two-centimeter deluge in about two hours, a stark contrast to the average of nine centimeters received on average each year. The resulting flash floods soon stirred up the mud avalanche that destroyed much of Leh and nearby villages.

Monasteries, monks and nuns appear to be only segment of society Mother Nature has spared. "We are all okay, and we are helping all those who are still alive," a senior monk, Konchok Samten Lama, told Asia Times Online on August 8 via a satellite phone link, by then the only form of telecommunications with Ladakh. Volunteers, foreign tourists among them, were helping a traumatized population, including thousands left homeless.

About two decades of tourism-related developments and infrastructure lie buried in the mud. Casualties include the two highways connecting Leh to the rest of India - to Srinagar and to Manali, two of the highest roads accessible by motorized vehicles in the world. Also gone are hospitals, schools, TV and phone communication systems, small bridges and the Leh airport.[/quote]

It's becoming known as "The Year Mother Nature Went Crazy"

Welcome to By 2100!

This Blog is designed to be a Diary of Events illustrating Global Climate Change, and where it will lead.

Commentary is encouraged, but this Blog is not intended for discussion on the Validity of Climate Change.

Category Labels

- Climate Events (85)

- Climate Solutions (45)

- Videos (42)

- Climate Statistics (39)

- The Deniers (34)

- Humour (15)

- Basic Information (5)

Wednesday, August 11, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

www.know-the-number.com

Our Climate is Changing!Please download Flash Player.

No comments:

Post a Comment